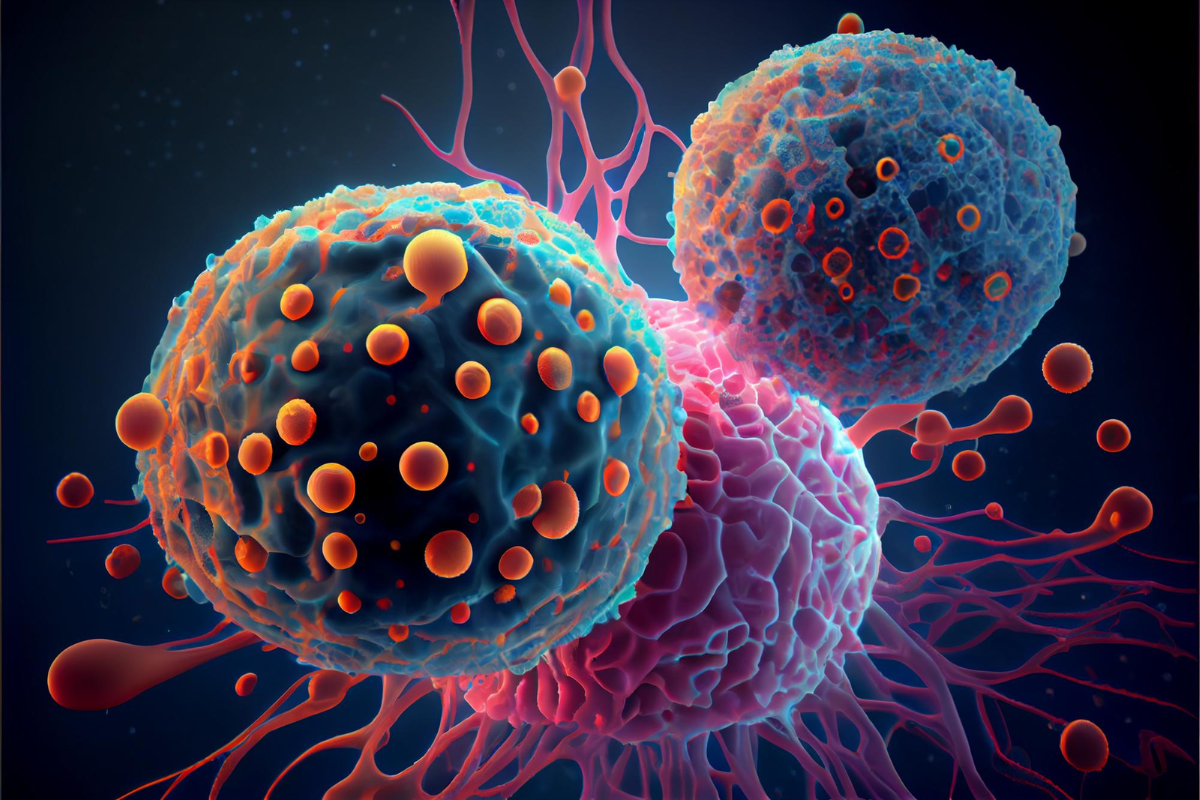

A survey was done in which thousands of advanced cancers indicated a way to detect those that respond to revolutionary therapies that unleash an immune response against tumours. However, the results show difficulty level to translate an approach into a reliable clinical test. The findings are the latest evidence to indicate that tumours having a large number of DNA mutations are more likely to respond to immunotherapies than are cancers with fewer mutation and result in longer survival for people who receive treatment.

Finding a threshold

But the immune system is intricate, and it has proved difficult to decide what makes one tumour vulnerable to treatment but allows another to escape without damage. One hypothesis is that a tumour that is more genetically different from normal tissue, the more likely it is that the immune system will recognize and eliminate it.

It’s complicated

Though it is not impossible it could add to the complexity of an already complicated test. Counting up mutations in tumour genomes involves sequencing of either the whole genome or sections of it. Different DNA sequencing methods and algorithms for understanding the resulting data can give conflicting results. And it’s vague that if all mutations should be valued equally, or only some are likely to prompt an immune response than others.

Albeit some pharmaceutical companies have started to include tests that gauge the number of mutations in a tumour in clinical trials of their immunotherapies. But this could be due to a number of factors, such as where the company drew the line between high and low numbers of mutations.

Ultimately, it is supposed that a combination of characteristics is taken, including mutation counts and information about the concentration of a given protein to select patients for immunotherapy.

-Agonist.png)