The Promise of NK Cells: A Novel Approach to Immunotherapy

Nov 22, 2024

Table of Contents

NK cell therapies have demonstrated significant clinical efficacy, with studies reporting response rates ranging from 40% to 80% in certain hematologic malignancies. As of recent data, several NK cell therapy candidates are in clinical trials, with notable successes including improved overall survival rates and reduced adverse effects compared to traditional treatments.

Understanding NK Cells and Their Role in Immunity

Natural killer (NK) cells are a type of lymphocyte essential to the innate immune system. These cells are highly selective in targeting and play a critical role in the body’s defense against tumors and virus-infected cells. NK cells contain cytotoxic granules within their cytoplasm, packed with specialized proteins like perforins and granzymes. Perforins create pores in the membranes of target cells, allowing granzymes to enter and trigger cell death. NK cells originate from common lymphoid progenitor cells, which also give rise to B and T lymphocytes. They develop and mature in the bone marrow, lymph nodes, spleen, tonsils, and thymus before circulating in the bloodstream.

Downloads

Article in PDF

Recent Articles

- Actinium Announces SIERRA Trial Results; Santhera Seeks FDA Review for Vamorolone; Seres Announce...

- FDA Grants Orphan Status to MDL-101 for LAMA2-CMD; Pfizer’s ABRYSVO Approved for High-Risk Adults...

- New cancer drug tested in mice may benefit certain leukaemia patients

- Cilta-cel Demonstrates Prolonged and Deep Responses across Advanced Treatment Lines, Signifying P...

- Analyzing the Most Promising Drugs That Will Lose Patent in the US & EU in 2022

Mechanism of Action of NK-cells

The NK cell surveillance system relies on various activating and inhibitory receptors on the cell surface, which regulate NK cell cytolytic activity by delivering either activating or suppressive signals. The final action of NK cells is determined by a delicate balance between these signals. Inhibitory receptors bind to self-MHC class I molecules found on all nucleated cells, enabling NK cells to recognize and spare normal cells. Additionally, NK cells are powerful producers of inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IFN-γ.

NK Cells in Cancer

NK cells were first discovered in mice in 1975 as a unique subgroup of lymphocytes capable of targeting and destroying tumor cells without prior sensitization. Since their discovery, NK cells have become a focal point in oncology research. Years of dedicated research have deepened our understanding of NK cell biology, largely informed by the concepts of ‘missing-self’ and ‘induced-self’ recognition. Unlike their close relatives, T and B cells, which recognize foreign antigens, NK cells are specialized in sensing changes in self-molecules on the surface of the body’s own cells. This “self-centered” recognition makes NK cells particularly well-suited for cancer therapy, as cancerous cells typically arise from abnormalities in normal cell function. The ‘missing-self’ model explains how NK cells specifically avoid targeting normal cells by recognizing and sparing those expressing MHC I molecules, thus focusing their cytotoxic activity on cells lacking these markers.

Types of NK-based Immunotherapy

NK cell-based cancer immunotherapy focuses on restoring the impaired function of NK cells seen in cancer patients and on enhancing and sustaining their activity against tumors. These therapies can either stimulate the body’s own NK cells or provide NK cells externally through methods like hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or adoptive cell therapy.

Early NK cell immunotherapies sought to boost the natural antitumor activity of NK cells by activating them and promoting their expansion in patients. A primary method involved administering cytokines such as IL-2, IL-12, IL-15, IL-18, IL-21, and type I interferons. Under cytokine stimulation, NK cells transform into Lymphokine-activated Killer (LAK) cells, exhibiting increased cytotoxicity against cancer cells along with heightened levels of effector molecules like adhesion molecules, NKp44, perforin, granzymes, FasL, and TRAIL, as well as enhanced proliferation and cytokine release. Despite this, the antitumor effects of this approach remain limited.

NK Cell Therapy: Target Patient Pool

Each year, nearly 10% of new cancer diagnoses in the United States are hematologic malignancies, such as leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma. Acute myeloid leukemia is a form of acute leukemia marked by the buildup of malignant, immature white blood cells. AML is the most prevalent type of acute leukemia in adults, accounting for 80-85% of cases, and is also the second most common and most fatal form in children. The prognosis for AML is poor, with a five-year survival rate of just 30.5%, primarily due to the lack of highly effective treatment options.

B-cell lymphomas make up most (about 85%) of the non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the United States. These types of lymphomas start in early forms of B lymphocytes. The total number of incident cases of multiple myeloma in the US was 30,000 in 2023, which is expected to increase by 2034, as per the DelveInsight analysis.

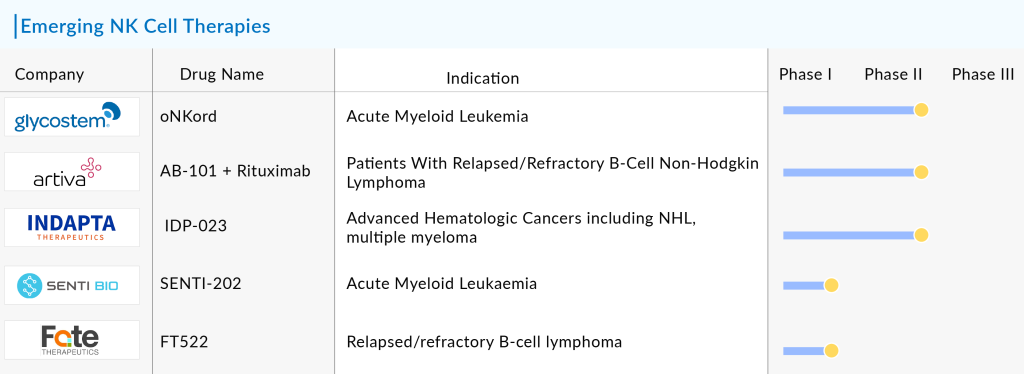

Promising NK Cell Therapies in Clinical Development

Immunotherapies based on NK cells are gaining growing attention in cancer treatment. Preliminary clinical trials have demonstrated encouraging results, with good efficacy and safety profiles. NK cells are crucial in managing and potentially curing both solid tumors and blood cancers, such as acute myeloid leukemia and multiple myeloma. While NK cell therapy has not yet received approval from the US FDA for treating any specific cancer, ongoing clinical trials are working to enhance the technique’s effectiveness.

Some of the potential NK cell therapies in the pipeline include AlloNK (Artiva Biotherapeutics), oNKord (Glycostem), FT522 (Fate Therapeutics), IDP-023 (Indapta Therapeutics), and SENTI-202 (Senti Bio), among others.

The anticipated launch of these emerging NK cell therapies are poised to transform the market landscape in the coming years. As these cutting-edge therapies continue to mature and gain regulatory approval, they are expected to reshape the NK cell therapy market landscape, offering new standards of care and unlocking opportunities for medical innovation and economic growth.

Additionally, NK cell therapies could pave the way for personalized medicine, allowing for tailored treatments based on an individual’s specific tumor profile. With the potential to improve survival rates and quality of life for cancer patients, the launch of NK cell therapies is an important step toward transforming cancer care and expanding the scope of immuno-oncology.

NK Cell Therapy: Challenges and Future Outlook

NK cell therapy presents a promising avenue in cancer immunotherapy, yet it faces several critical challenges. One major hurdle is the limited persistence and proliferation of NK cells once introduced into the patient’s body. Unlike T cells, NK cells generally lack long-term memory, which means they do not last or replicate effectively within the host after administration. Consequently, achieving a sustained therapeutic response often requires multiple infusions, which can be costly and difficult to manage clinically.

Additionally, the limited infiltration of NK cells into solid tumors poses another obstacle. The tumor microenvironment (TME) is often suppressive and physically restrictive, hindering NK cells’ ability to migrate and penetrate tumors effectively, which limits their anti-tumor efficacy, particularly in solid cancers.

Another significant challenge is the immune evasion mechanisms employed by tumors, which can impair NK cell activity. Cancer cells often downregulate ligands that activate NK cells or upregulate inhibitory signals that reduce NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Furthermore, immunosuppressive cells within the TME, such as regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), can inhibit NK cell function, making it difficult for these cells to mount an effective immune response.

Manufacturing NK cells for therapy at a clinical scale also presents logistical difficulties, as large quantities of cells must be cultured and activated ex vivo, a process that is technically demanding and expensive. These obstacles underscore the need for innovative strategies in NK cell therapy, including genetic modifications to improve persistence, methods to enhance infiltration into tumors, and approaches to counteract the immunosuppressive TME.

However, the field of NK cell therapy is advancing rapidly, driven by innovations in genetic engineering, combination therapies, and immune checkpoint inhibition. Researchers are exploring ways to combine NK cell therapy with other forms of immunotherapy, such as checkpoint inhibitors and CAR-T cells, to improve overall treatment efficacy. Additionally, enhancing the functionality of NK cells through cytokine support or engineered receptor expression is paving the way for more potent and durable therapies.

With the increasing understanding of NK cell biology and the improvements in cell engineering, NK cell therapy is expected to become an essential part of the oncological treatment landscape. The hope is that these therapies will eventually lead to off-the-shelf cancer treatments that are accessible, effective, and safe, transforming the way we approach cancer treatment.

Downloads

Article in PDF

Recent Articles

- EPCORE NHL-1 Trial Reveals Promising Response Rates for Investigational Follicular Lymphoma Thera...

- Pirtobrutinib Monotherapy: A Promising Beacon of Efficacy and Safety in Relapsed/Refractory Folli...

- Unleashing the Potential: CD38 Directed Therapies Revolutionize Multiple Myeloma Treatment

- AKT Inhibitors: A potential Cancer Immunotherapy Target

- Bayer’s AskBio Initiates Phase II GenePHIT Trial; FDA Approves Merck’s KEYTRUDA Plus Chemoradioth...